Parts of the following

have been excerpted from the University of Virginia education program.

Please read the following and respond on a separate document (send or hand in) the questions that follow. This is to assure that you have actually read. There will be no further assessment. Your responses are due by the close of class on Tuesday.

Please read the following and respond on a separate document (send or hand in) the questions that follow. This is to assure that you have actually read. There will be no further assessment. Your responses are due by the close of class on Tuesday.

I) A Brief History of Cartoons

While caricature originated around the Mediterranean, cartoons of a more editorial nature developed in a chillier climate. The Protestant Reformation began in Germany, and made extensive use of visual propaganda; the success of both Martin Luther's socio-religious reforms and the discipline of political cartooning depended on a level of civilization neither too primitive nor too advanced. A merchant class had emerged to occupy positions of leadership within the growing villages and towns, which meant that a core of people existed, who would respond to Luther's invectives and be economically capable of resisting the all-powerful Catholic Church. In regards to the physical requirements of graphic art, both woodcutting and metal engraving had become established trades, with many artists and draughtsmen sympathetic to the cause. Finally, the factor which probably influenced the rise of cartoons more than any other cultural condition was a high illiteracy rate. Luther recognized that the support of an increasingly more powerful middle class was crucial to the success of his reforms, but in order to lead a truly popular movement he would need the sheer weight of the peasantry's

An excellent example of Luther's use of visual protest is found in two woodcuts from the pamphlet "Passional Christi und Antichristi", originally drawn by Lucas Cranach the Elder. These two images contrast the actions of Jesus with those of the Church hierarchy; the hegemony of religion at the time ensured that when someone drew a Biblical episode like that of Jesus driving the moneychangers out of the Temple, everyone would recognize it.

Undoubtedly, Nast was the

greatest popular artist of the Civil War; Lincoln was frequently quoted as saying

Nast was his best recruiting sergeant, and his scenes of once-thriving southern

cities like Richmond did much to convey the magnitude of destruction to

Northern audiences.

(Does this remind you of any paintings?)

After Nast became the featured cartoonist at Harper's much of his art was focused on the local New York scene. The primary shortcoming of Nast's work overall is that the quality of his satire never matched the quality of his art.

Joseph

Keppler became the most commercially and critically acclaimed cartoonist of the

Gilded Age. Shortly after his arrival in America in 1867 Keppler

"fell in with a distinguished crowd of journalists, writers, and

artists"-- including a young reporter named Joseph Pulitzer. Keppler

and his associates had established an important connection with the local

populace, relying heavily on international affairs and German-ethnic comedy. Unlike Nast's coarse etchings, Keppler's cartoons reflected "a

grace of artistic approach" derived from his exposure to popular

Austro-German styles of the day.

Keppler

held that unscrupulous lawyers only encourage frivolous lawsuits. The family is

destroyed: babies are abandoned in their nest; mother and father are carried

off in opposite directions, delivered into the clutches of their respective

lawyers.

Keppler's

views of the family and women's rights were more traditional than progressive in this regard.

The success of a

political cartoon rests in its ability "to influence public opinion

through its use of widely and instantly understood symbols, slogans,

referents, and allusions". "People cannot

parody what is not familiar" to the audience; so the best

cartoons incorporated popular amusements which emerged after the Civil War, as

well as universally-recognized themes from the Bible, Shakespeare, and other

"classic" sources.

The success of a

political cartoon rests in its ability "to influence public opinion

through its use of widely and instantly understood symbols, slogans,

referents, and allusions". "People cannot

parody what is not familiar" to the audience; so the best

cartoons incorporated popular amusements which emerged after the Civil War, as

well as universally-recognized themes from the Bible, Shakespeare, and other

"classic" sources.President Chester A. Arthur

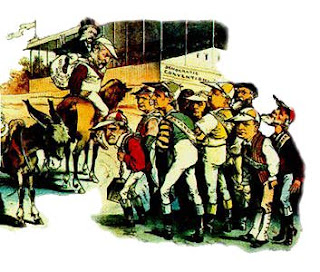

Cartoons concentrated on political activity, its

artists tried to reflect facets of that environment's general atmosphere and

distort them in such a way as to illuminate particular criticisms. For many

years sports had been one of the favorite cartoon metaphors for politics. The

detail from "The Political Handicap" is such an example, as its

parody lies in the comparison of equestrian ability and effectiveness on the

campaign trail. The image juxtaposes 1880 Republican presidential nominee James

A. Garfield's confidence in the saddle with the indecisive Democrats, who had

been unable to elect one of their own

since James Buchanan in 1856.

Please respond to the following questions, as pertains to the above material. These are due at the end of class on Tuesday.

1 What are the two elements that make up a cartoon?

2. What was the purpose of Da Vinci's "Ideal of Deformity"?

3. What was the purpose of the original caricaturas?

4. Why were caricatures an effective way for Martin Luther to communicate his message?

5. Take a look at Cranach's caricature. (look, carefully) Why in particular would have the populace related to this image?

6. What was the original purpose of Franklin's cartoon?

7. How was it later adapted?

8. What three elements made Thomas Nast's work so effective?

9. Why did Lincoln find Nast's cartoons an effective tool for his political agenda?

10. In a minimum of 25 words, explain the message in Nast's "Emancipation"?

11. What are some of the images Keppler uses to how lawyers are corrupt?

12. Discuss some of the problems with female emancipation, according to Keppler's view.

13. What type of people running for office when Chester A. Arthur was president?

14. Look at the Garfield comic. What type of animal are democratics riding on and what is the message being conveyed?

Another trait of the

political arena that held a great deal of weight with the masses was its

emphasis on masculinity. One scholar of the era concisely describes the nature

of gender identity in this regard:

Late nineteenth century

election campaigns were public spectacles that ended for one side in triumph,

for the other in humiliation. Men described these contests through metaphors of

warfare and, almost as frequently, cock fighting and boxing. Victory validated

manhood.

In Conclusion

The decades of the nineteenth century after the Civil War, there emerged a political cultural rife with corruption and so provided the cartoonist with a fertile environment for spectacle and humor.

The decades of the nineteenth century after the Civil War, there emerged a political cultural rife with corruption and so provided the cartoonist with a fertile environment for spectacle and humor.

Please respond to the following questions, as pertains to the above material. These are due at the end of class on Tuesday.

1 What are the two elements that make up a cartoon?

2. What was the purpose of Da Vinci's "Ideal of Deformity"?

3. What was the purpose of the original caricaturas?

4. Why were caricatures an effective way for Martin Luther to communicate his message?

5. Take a look at Cranach's caricature. (look, carefully) Why in particular would have the populace related to this image?

6. What was the original purpose of Franklin's cartoon?

7. How was it later adapted?

8. What three elements made Thomas Nast's work so effective?

9. Why did Lincoln find Nast's cartoons an effective tool for his political agenda?

10. In a minimum of 25 words, explain the message in Nast's "Emancipation"?

11. What are some of the images Keppler uses to how lawyers are corrupt?

12. Discuss some of the problems with female emancipation, according to Keppler's view.

13. What type of people running for office when Chester A. Arthur was president?

14. Look at the Garfield comic. What type of animal are democratics riding on and what is the message being conveyed?

No comments:

Post a Comment